“Museums are important means of cultural exchange,

enrichment of cultures and the development of mutual understanding,

co-operation and peace among people”

(ICOM)

While celebrating International Museum Day (18 May) with the theme Cultural Landscapes and Museums, the life and work of South African old master JH Pierneef (1886 – 1957) should be of special interest, highlighting some key areas featured in the permanent exhibition of this artist’s work in the La Motte Museum.

JH Pierneef is acclaimed for his portrayal of the Bushveld, Lowveld, Highveld, Cape farmlands and Namibian landscapes. During the past few years his work has been subjected to criticism, mainly on the ground of the so-called ‘empty’ landscapes, ‘empty’ referring to the absence of figures and human activity in these spaces. One must, however, acknowledge and appreciate the approach the artist took towards the various subjects and themes. Pierneef worked purely through engaging with nature, portraying his interests by composing works that reflected natural beauty – trees, mountains, clouds and, lesser known works, of botanical features. If these works were to be classified in one of the three categories associated with defining Cultural Landscapes, they would fall under ‘Associated Cultural Landscape’, a type of landscape recognised by natural elements rather than material and cultural evidence. The cultural aspect might even be absent or insignificant.[1] This does not mean, though, that the physical landscape Pierneef portrayed is without any cultural significance; it should rather be seen from the perspective of the artist’s approach.

JH Pierneef (1886 – 1957)

Laeveld Mica, Oos-Transvaal, 1945

Oil on board, 48 x 62 cm

La Motte Museum Collection

Even though most of Pierneef’s work focuses on natural elements, culture did play an important role and is largely portrayed through architecture as a subject in his work. Pierneef’s fascination with architecture started when he was a young boy, sharing the interest with his father Gerrit Pierneef, a building contractor. Between 1908 and 1912, in Pretoria, Pierneef would sketch various houses of cultural importance and/or significance. These houses were owned mainly by ‘cultural icons’ such as Paul Kruger, General Erasmus, General Smit and Bishop Bousfield. Pierneef also sketched state buildings. During the sketching phase, some of these buildings were vacated and in line to be demolished.[2] Pierneef produced various lino cuts from these original ‘on the spot’ sketches during the 1920s and these became known as the ‘Old Pretoria’ series. It is significant that, even 30 years after some of these houses and buildings had been demolished, the Pretoria City Council commissioned Pierneef in 1948 and 1949 to paint eighteen of them for the Municipal Art Gallery collection (today some of the sketches and all these paintings are housed in the Pretoria Art Museum).

JH Pierneef (1886 – 1957)

Plaashuis met boom, (c. 1908 – 1912)

Mix media on paper, 17 x 28 cm

La Motte Museum Collection

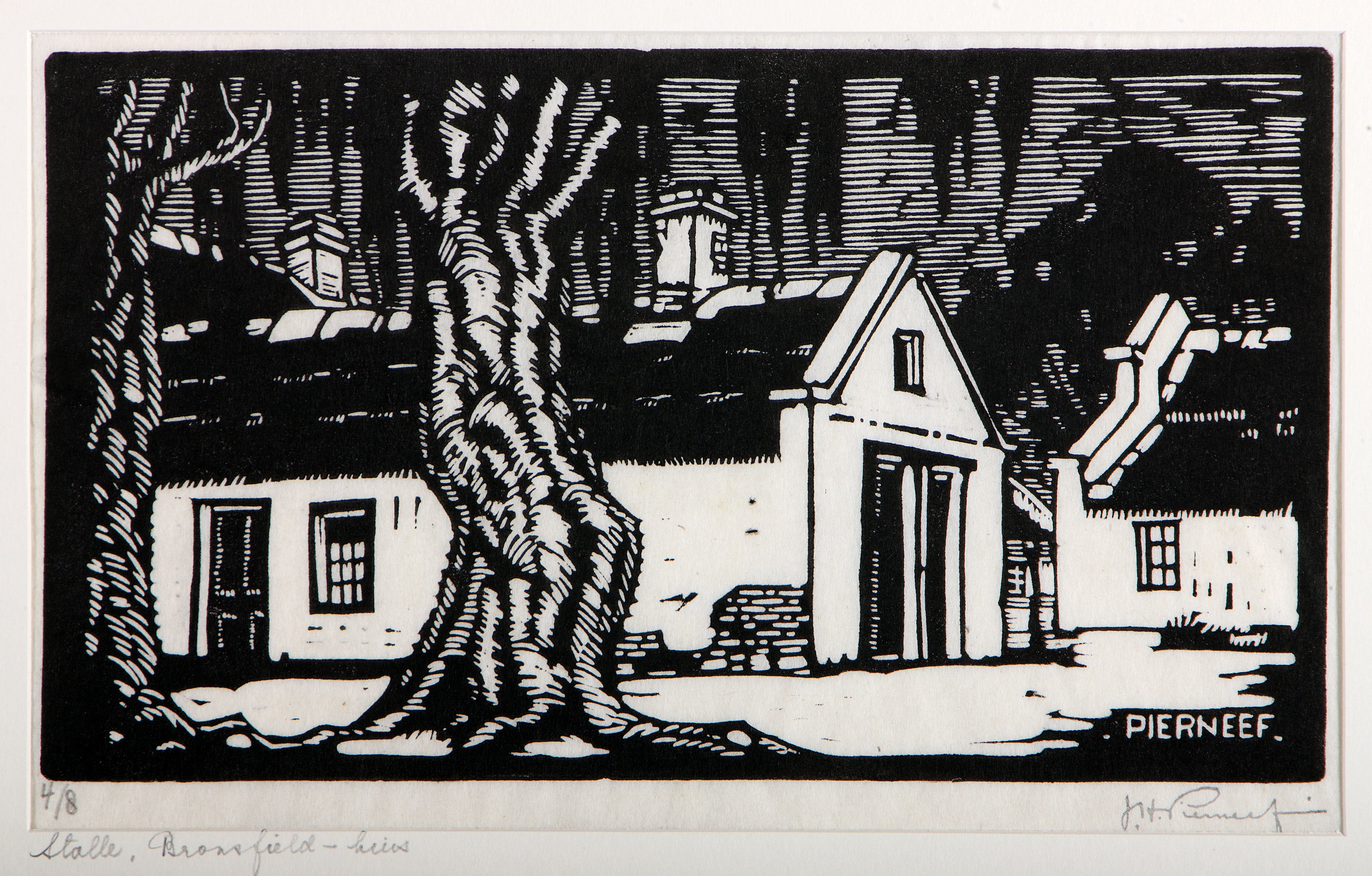

JH Pierneef (1886 – 1957)

Stalle, huis van Biskop Bousfield, Pretoria (c. 1920)

Lino cut, 14,7 x 25,8 cm

La Motte Wine Estate, Tasting Room

Another category of Cultural Landscape is described as ‘Clearly defined landscape designed and created intentionally by man’. Examples include parkland and garden landscapes created for sacred, religious or aesthetic reasons with the associated ensembles and buildings[3].

In 1939, Pierneef took his fascination with architecture further by designing and building his own house, with a landscaped garden, on the farm Mopanie just outside of Pretoria. He named his house Elangeni. The walls were erected from stones collected on the farm, using clay as ‘cement’. Thatch-grass served as roofing. The ‘house’ consisted of separate buildings, each a single room or living space, inter-leading with pathways. Inspired by the layout, the ‘house’ was nicknamed ‘die Kraal’.

Pierneef’s vision with Elangeni was to strive towards a purely South African architectural style, by incorporating various elements from different indigenous cultures and tribes. Right behind the house, Pierneef erected his studio that, on occasion, housed various important group exhibitions held with sculptor friend Fanie Eloff (1885 – 1947).[4]

Even though Pierneef had his own vision and approach when it came to portraying or creating a (cultural) landscape, the viewer will always be in the position to look at his work and interpret it from their own frame of reference, be it purely natural, cultural or even both.

[1] UNESCO. 2016. Cultural Landscapes, Operational Guidelines05. Annex 3.

[2] Pierneef, JH. 1949. I Love Old Pretoria, in The Outspan. 30 Sept. No.1179 (p22-23)

[3] UNESCO. 2016. Cultural Landscapes, Operational Guidelines05. Annex 3.

[4] Nel, PG. 1990. JH Pierneef : His life and his work. p.91 – 92